Some evenings I just sit there, watching as the night bleeds into the day, as the blue o’er purples to black and what strange dust, fleeted by the anonymous scurryings, resettles upon the trembling earth, ready for the coming of my weary feet. I sit there, thinking, watching.

I wish to be seen. I have been taught – as we all have – that I must be seen, or such a moment barely exists, barely matters, that the “Romantic” energy of my mediative solemnity will be lost. Such narcissism soon fades, however, as the day fades, as guilt takes over. But guilty as to what exactly…? As to the waste? The waste of what? I don’t even know… Of time perhaps, of the wasted and faded hour, of a life that has reached such a point as to allow for such a wasted moment?

The lax and unstringed minutes go springing off into the glistening dark. My back hurts. Unseen pain, experienced but not felt. I must go for my walk soon, but not yet, not quite yet. Another evening of steadily fading heat.

Beside me, my son strums his guitar. It is pleasant, mournful. My wife is berating him for his unfinished homework. Tipping back my chair, I look at them both. My wife’s face is red, and my son’s excuses are as mournful as any of his songs. Only seven years old, and already such a good liar. In the light I cannot see their strings, but they are there, plucked and twisted, urged ever onwards.

They keep at it, back and forth, until I shout, and my son gives up his hope. He goes to the table and, to the contentment of my wife, begins to work hard, writing furiously, almost pointlessly for the fury of it. And I, ashamed of my outburst, ask myself: would they even understand? Would any even understand? Were I to speak again, saying, crying rather, that such a mountain of paper, of long years struggle will only conclude in failure? I will say: the grand cycle of life remains inculminated, forever unfinished, forever derided, that unspeakable outrage that nothing can be done though all done, laughing in the dark, crying.

Will they listen?

Will they disbelieve as they have always disbelieved?

But where comes such feelings?

Where?

They are sitting at the table now. My wife is helping. Without looking up, she asks: “When are you going for your walk?”

“Soon,” I say.

She doesn’t answer.

She’s worried about me. The desk that destroys life, the sitting soul.

I am sitting still though. For it is still quite light out, a purple sky quite fragrant of grapes and petroleum, I’m sure. Deep down, I believe, I am trying to excuse myself. It is too hot perhaps? Perhaps I have not read enough? I have indeed been busy today and the tank of knowledge is almost empty.

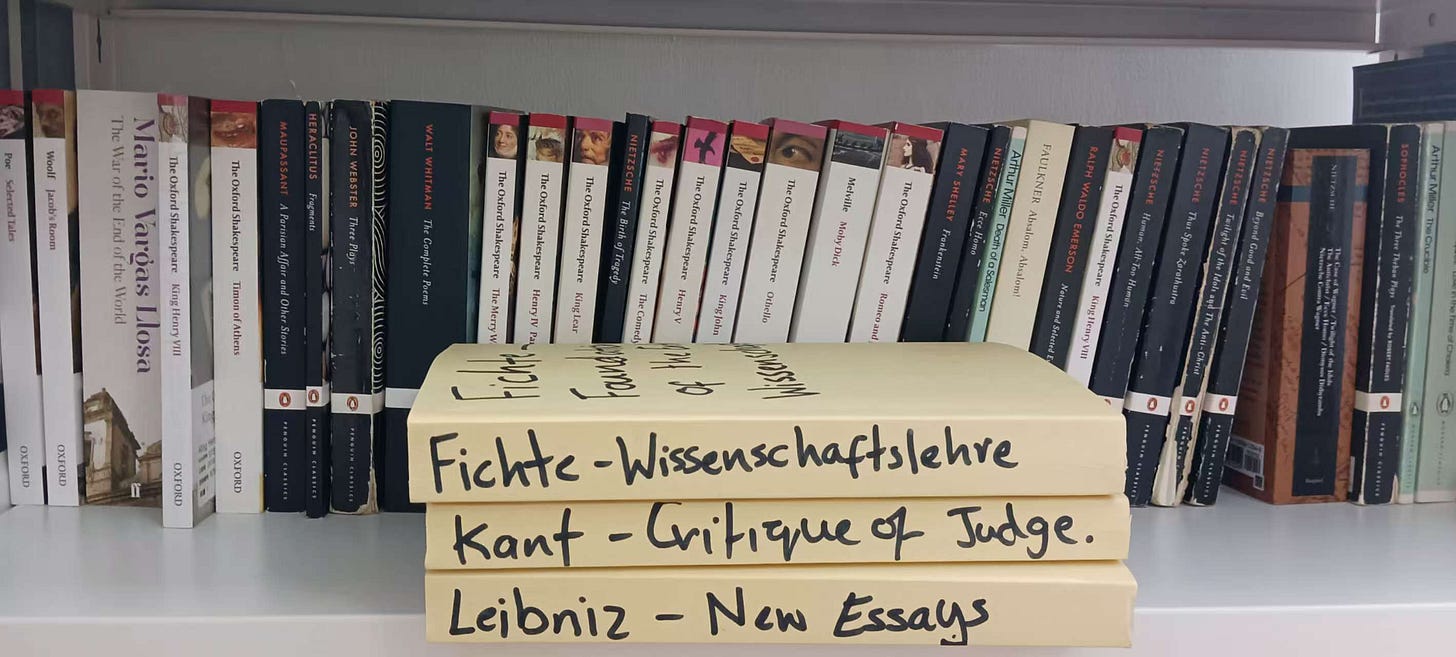

I look to my books. They lie beside me, waiting. Cheap facsimiles, privately printed. Their covers are light, unpatterned primary colors, and along their spines I have written, in my clumsy hand, their titles — thick black lettering to match their supposed depths:

Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre

Leibniz’s New Essays on Human Understanding

Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment

Together they mean something. Though I’m not sure what, or why precisely these are out of the many others. They make me happy though: this great and stolen knowledge. I am a philosopher. Surely? I have earned the right to believe as much. Right? I am laughing at myself. And yet their weight is inimical, my incomprehensibility of their ideas everlasting. I could read them a hundred times and still there will be something not understood, something lost in those thousand pages, that labyrinth of tightknit idealism.

I look. They are not watching.

Within the noumena lies the minotaur of ethics. Smart, I think, very smart. But then why do they go on, utterly unaware? It is my fable of the cunning hour. Laughing at myself still. Ohoho. Wage du zu irren und zu träumen. The erring dream. Now that really is genius. Really, really well remembered.

I pick up the Wissenschaftslehre. Its cheap glue is ticklish and intriguing: it binds the moment in me. I flip to a random page. I begin to read:

According to what has been said, this manner of acting is supposed to be separated as such from all that it is not, and this separation is supposed to be accomplished by an act of reflective abstraction. This abstraction occurs freely. The human mind is not led to engage in such abstraction by any blind compulsion. The entire difficulty is thus contained in the following question: What rules guide freedom when it is engaged in this act of separating? How does the human mind know what it is supposed to accept and what it is supposed to ignore?

The mind lies mystified. I blink over the passage, mystified. To accept or to ignore…? I read again. I attempt by brute force to comprehend, what with my dull and sleepy mind, remains incomprehensible. I do not dare put the book down – defeat would be worse. And yet there is something to this… somewhere within an incorrigible weight… waiting… to accept or to ignore…? threatening something incorrigible…. it is the weighting of an incorrigible threat… the threatening of an incorrigible wait… the weighting… and, beginning to nod, I, the spectral decadent that I am, begin to dream…

I was in the brute land, and I saw a light and this light was strange for, although the sun was high, the world was filled with the shadows of twilight. A wind was blowing, and it was this wind that swept the land and left the thorns chattering in its wake. I walked along a narrow road, and it was in the sadness that the beast met me. I looked and I was afraid for the beast was like none I had ever seen. For although the body was that of a lion it had the head and tail of a snake. It moved and in its movement was the fury of fire as its bright claws stripped the lean earth and scatted the shadows of the earth, though in its shadow lay the odor of the lily and the sleep of the unfathomable waters whose peace is eternal. I looked and it was then that the beast spoke. Its language was that of the dream, and this I did know, for it spoke with those signs of faded star fire. It said it knew what I sought, what I had always sought in those long and faded steps of mine. It pointed me towards a lake. Thankful to it and bowing solemnly, I then crossed that weary land until I reached those cool and lilac banks that I had been promised. Amongst the reeds I found what I was seeking: a yahoo: a human-baboon. Its haunches were dipping rhythmically in the water. It was soiling itself and howling with delight. Music was coming from somewhere, a soft jangling from out that twilight. I touched its shoulder, and it stopped its howling, and rose to a height I did not think its ape’s body could rise to, and when it turned there was a moment as of starburst or the beat of the bumblebee’s wing, so grand and yet fragile for all its grandeur, for the face I met was my own. I was breathless and afraid. But this did not last for suddenly I too was touched on the shoulder and, turning, I was met again by myself, and I looked and forever – as though caught between two mirrors – I saw myself endlessly, repeated endlessly until I could not even say that I was I but a range of Is that never ended and it was so hot and I was afraid and it meant something and I was so close and-

“What is wrong with you!” my wife screams. “Why don’t you understand? Why!?!”

She is scolding my son. His poor math. They are arguing. I tell them the shut up. But it is too late. They go on in Chinese, not listening.

Suddenly I can smell myself. I have been sweating in my dream. For while I slept, my wife turned off the air conditioner. Now I’m really not going for a walk. A taste of my early death for her, or so she’ll think… And inculminated is a dream word! A nonsense word! Fool!

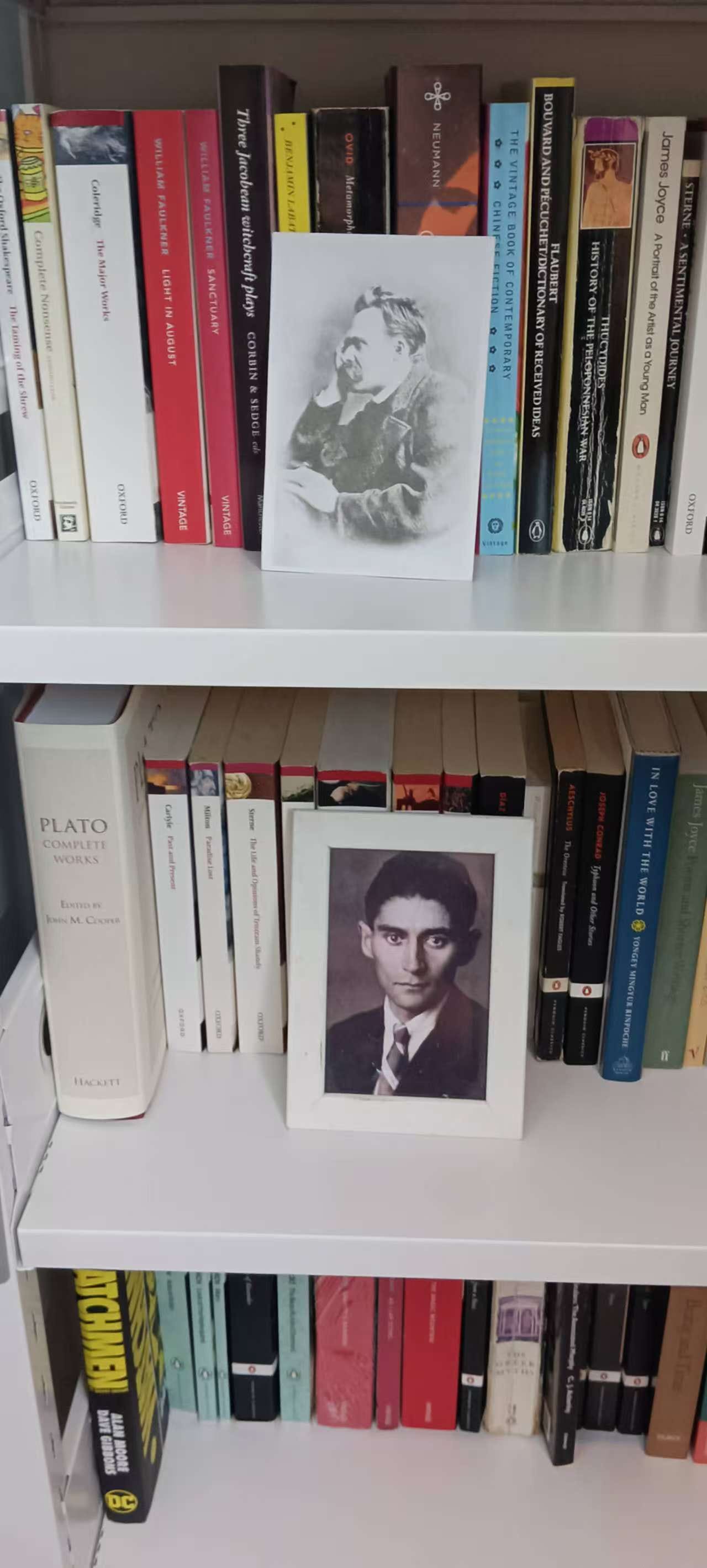

The brutality of the moment calls for the symbolic. I want to get up and put the portrait of Kafka above Nietzsche’s. This is one of my madnesses. It is what I do when I am in one of my funks, one of my midnight moods, when the depression strikes and speaking feels like a death sentence for the feeling of tears that wells from somewhere unknown. The rise of misery… the denial of life… it’s all feeling in the end. The stern slightly mocking menace of Kafka. Laughing at me, trying to teach me to laugh while I barely feeling anything except pure dishonesty: tied to my desk, a life not wished. But then what life ever was? The voice that urges nothing but suicide. A three-day bout, sometimes four, and it all ends as suddenly as it began. The despair passes and Nietzsche rises again.

Nietzsche? – but he is more of a promise than a reality.

They’ve finished the math and are up from the table now. My son is standing by the window, my wife by the bedroom door. They are throwing a stuffed toy back and forth. Always back and forth. The toy is a Capybara. His name: fàngpì. This means fart in Chinese.1 And his flyings are just as distasteful to me, just as aggravating, stinking of hypocrisy as they do…

Listen. My wife worries about two things in her life: that my son’s endless studies will damage his eyes and that, due to his not studying enough, he will do poorly in school. You can see what a bind this puts her into, what wicked dreams she must awake from sweating every night. This is one of her little madnesses. This is the two stars which she orbits: the eye vs the A. And yet my own stars await.

I look at Nietzsche. He is not looking at me. He is faced away. He with his own void, his own monsters. Let us consider. Let me at least try to get something going…

Here: Nihilism is the ghost that haunts the feast of modernity. But really, one must ask oneself, why not be a true nihilist and that is not even believe that something needs to be believed in? Why be sad that life has no meaning? For this is still a belief, an ideology… That one must be sad when confronted by certain facts, that this cause must have this particular effect. Why? Why not another effect? Why not happiness? Why not striving? Why not fun? Because we are still captured by that slave idea that our suffering must have a meaning. This is still belief. Only nihilism in name, not fact. This is the true genius of Nietzsche, this is the good news of that modern Heraclitus, the last Dionysian: reality does not need to be redeemed. There is nothing implicitly wrong with it and we do not need to react with such maudlin self-sadness, such self-judgment. We bring our sadness as to the unknown as the only certainty we have and celebrate it – let us rather celebrate life! And any who would teach you the opposite are slaves themselves and wish for nothing but-: fàngpì hits me in the head as he does most nights…

My wife and son are laughing at me. In the moment I could turn away and sink to self-pity. I could tell them to stop it. But instead, I begin to laugh. For once, I am laughing, and it is right and true. It is good. It is the desk that destroys life, I think, but the walk that brings it back, that will let me celebrate the life I could so easily abscond from and cry over. It is dark now, cool enough, and nascent stars sugar o’er what would be bleak if we were not here to wonder at them. I am getting up. My wife is studying something, feeding her usual hypochondria. But it is fine. It is right. I am putting on my shoes. My son is settling once again to his guitar. The night: a promise of a promise. The steps that beat out the poetry of thought, the unstringed minutes that jingle to another as one unseen, but happy moment passes to another…

“I’ll be back soon,” I say, always.

“Be careful,” my wife says as she always does. “Don’t get lost.”

How could I? I think.

******

I hope you found something in this. I have decided once a month to try and set down a few scraps from my life — the walks not taken, the books half-read, the laughter and the gloom in equal measure. Nothing resolved, of course, but perhaps worth the telling. Would love to hear your feedback! And what you would perhaps like me to write about next… I’m always desperate for ideas!

******

Also, if you enjoyed this even a modicum please share, you would do me a world of favors. A modicum for a world: an unbounded generosity!

I don’t remember why he has this name: part of the forgotten mythos of family.

When I feel overwhelmed by the state of the world and my inability to make progress on an intellectual level, I throw myself into manual labor. There's always something to do in the garden—pulling weeds, feeding the chickens, walking the dog, playing soccer with the kids... All of this grounds me and clears my head. And yes, it also helps me not take myself and the world so seriously.

Why be in such a lugubrious mood when you can be a simpleton?